Les ingénieurs électriciens de l'Université de Duke

ont développé un système de télémétrie sans fil, léger mais assez

puissant pour permettre aux scientifiques d'étudier l'activité

neurologique complexe des libellules lorsqu'elles capturent leurs

proies.

Jusqu'à

présent, les études passées sur le comportement des insectes ont été

limitées par la difficulté de collecter des données et les méthodes sont

trop lourdes pour leur permettre d'agir de manière normale, comme ils

le font dans la nature. Le nouveau système n'utilise pas de batteries,

mais plutôt envoie le courant par rayon à la libellule qui vole.

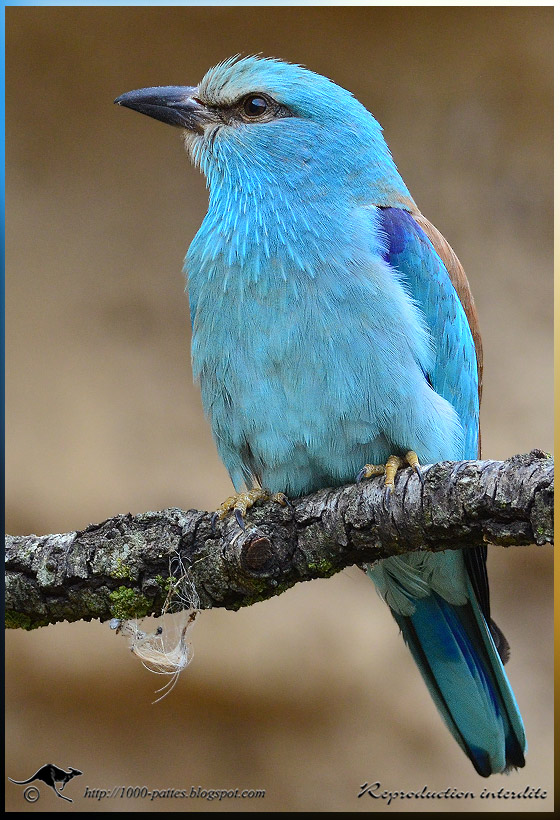

Cordulie bronzée, mâle en observation

Cordulia aenea - Cordulidae

Downy emerald

En

essayant de mieux comprendre le système de commande du vol complexe

des libellules, ces ingénieurs collectent leurs informations en

attachant des électrodes minuscules aux cellules nerveuses

individuelles dans le système nerveux de la libellule et

enregistrant l'activité électrique des neurones de la libellule et des

muscles. Des systèmes existants pour enregistrer l'activité neurale

exigent des batteries beaucoup trop lourdes pour être portées par une

libellule; les expériences ont donc jusqu'à présent été effectuées avec

des libellules immobilisées.

Libellule déprimée, femelle en ponte

Libellula depressa - Libellulidae

Si

le nouveau système s'avère fructueux, les chercheurs s'attendent à ce

que de nouvelles et passionnantes possibilités dans le comportement de

petits animaux s'ouvrent pour la première fois:

Les chercheurs ont développé un système sans fil qui évite la taille et le poids d'une batterie.

Le

système fournirait assez de puissance à la puce attachée à une

libellule volante pour qu'il puisse transmettre en temps réel les

signaux électriques d'un grand nombre de ses neurones.

Libellule fauve mâle en observation

Libellula fulva - Libellulidae

Le

système pourrait envoyer assez d'énergie depuis la puce pour permettre

de renvoyer des masses de données à plus de cinq mégabits par seconde,

ce qui est comparable à une connexion à Internet privée moyenne. Les

scientifiques cherchent à synchroniser les données neuronales et les

réunir par le biais de la puce à une vidéo haut débit alors que

l'insecte est en vol.

La

puce, avec deux antennes fines comme des cheveux sera fixée sous

l'insecte pour ne pas gêner le mouvement de ses ailes, la puce devant

avoir un contact radio ininterrompu avec l'émetteur.

Orthetrum réticulé femelle en ponte

Orthetrum cancellatum - Libellulidae

Black-tailed Skimmer

Flight of the dragonfly:

Past studies of insect behavior

have been limited by the fact that today's remote data collection, or

telemetry, systems are too heavy to allow the insects to act

naturally, as they would in the wild. The new system uses no

batteries, but rather beams power wirelessly to the flying dragonfly.

Duke electrical engineer Matt Reynolds, working with Reid Harrison at

Intan Technologies, developed the chip for scientists at the Howard

Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI), who are trying to better understand

the complex

flight control system of dragonflies. They gather their information by attaching tiny electrodes to individual nerve cells

in the dragonfly’s nerve cord and recording the electrical activity

of the dragonfly's neurons and muscles. Existing systems for recording

neural activity require large batteries that are far too heavy to be

carried by a dragonfly, so experiments to date have been carried out

with immobilized dragonflies.

If

the new system proves successful, the researchers expect that broad

new avenues into studying behavior of small animals remotely will

become available for the first time.

“We

developed a wireless power system that avoids the need altogether for

the size and weight of a battery,” said Reynolds, assistant professor

of electrical and computer engineering at Duke’s Pratt School of

Engineering. He presented the results of his work today at the annual

Biomedical Circuits and Systems Conference, held by the Institute of

Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) in San Diego.

“The

system provides enough power to the chip attached to a flying

dragonfly that it can transmit in real time the electrical signals from

many dragonfly neurons,” Reynolds said.

The

chip receives power wirelessly from a transmitter within the flight

arena in which the experiments are carried out. The system can send

enough power to the chip to enable it to send back reams of data at

over five megabits per second, which is comparable to a typical home

internet connection. This is important, the scientists said, because

they plan to sync the neuronal data gathered from the chip with

high-speed video taken while the insect is in flight and preying on

fruit flies.

“Capturing

this kind of data in the past has been exceedingly challenging,” said

Anthony Leonardo, a neuroscientist who studies the neural basis of

insect behavior at HHMI’s Janelia Farm Research Campus in Virginia. “In

past studies of insect neurons the animal is alert, but restrained,

and observing scenarios on a projection screen. A huge goal for a lot

of researchers has been to get data from live animals who are acting

naturally.”

The average weight

of the dragonfly species involved in these studies is about 400

milligrams, and Leonardo estimates that an individual dragonfly can

carry about one-third of its weight without negatively impacting its

ability to fly and hunt. Currently, most multi-channel wireless

telemetry systems weigh between 75 and 150 times more than a

dragonfly, not counting the weight of the battery, which rules them out

for most insect studies, he said. A battery-powered version of the

insect

telemetry system, previously developed by Harrison and Leonardo, weighs 130 milligrams -- liftable by a foraging dragonfly but with difficulty.

The

weight of the chip that Reynolds and his team developed is just 38

milligrams, or less than half of a typical postage stamp. It is also

one-fifth the weight and has 15 times greater bandwidth of the previous

generation system, Reynolds said.

The

researchers expect to begin flight experiments with dragonflies over

the next few months. The testing will take place in a specially

designed flight arena at HHMI's Janelia Farm complex equipped with

nature scenes on the walls, a pond and plenty of fruit flies for the

dragonflies to eat.

The chip,

with two hair-thin antennae projecting from the back, will be attached

to the belly of the insect so as not to interfere with the wings.

Since the chip must have uninterrupted radio contact with the power

transmitter on the ground, the

chip is carried much like the backup parachute on the underside of the animal.